An unconventional approach

Sir James believed in the importance of testing business theories and ideas in the market place, and changing those that did not work. He was as ruthless with conventional wisdom as he was with his own theories: any found to be unsuccessful in practice were discarded and new ones tested in their place. This willingness to adapt his ideas to changing situations, combined with his ability to take well calculated risks and his extraordinary energy are, perhaps, what made him such an exceptional businessman.

As Tobias Brown put it, the young American who Sir James took on to run the Hong Kong office of General Oriental in the 1990s, Sir James simply “had an amazing mind”.

“He just absorbed huge quantities of information and asked for more. He was a reverse thinker, which he always reckoned was a result of his lack of a formal education.”

Maverick

“If you see a bandwagon, it’s too late to get on it”

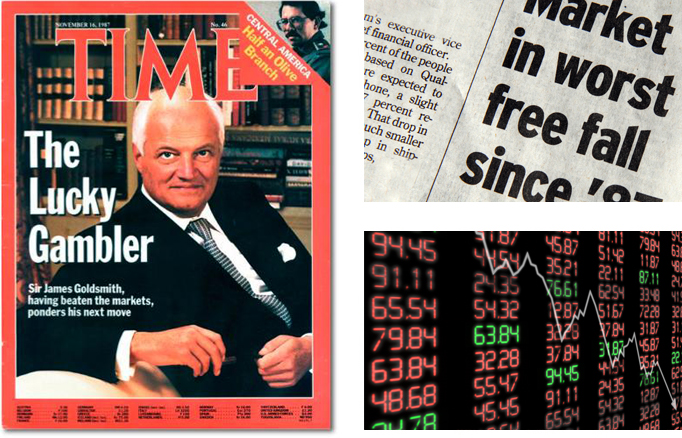

Sir James predicted numerous significant stock market events: the UK market boom of 1971-2, the financial crash of the mid 1970s and the boom again of the early 1980s, and the big crash in 1987. In all of these cases, he was able to invest when the time was right and then liquidate his assets prior to a crash – a strategy that guaranteed his survival when many other major financiers were wiped out.

He made most of his money in bear markets, buying Cavenham out in the 1970s when the markets were at rock bottom, and getting into timber when the American economy was at its weakest. He also utilized the bull market to full effect in 1971 to 1973, with his takeover of Bovril, and subsequent bid for Allied Suppliers and a series of smaller acquisitions, before liquidating his assets just before the crash.

He later became a celebrity in the US for being the man who not only anticipated the great stock market crash of October 19, 1987, but also profited from it. In anticipation of the crash he sold everything he owned, including his New York home, Grand Union, the London casino, Generale Occidentale and L’Express, timing the sale of his assets just weeks before disaster struck. This left him sitting on more than a billion dollars in cash and 1.5m acres of forest valued at $1.6bn when many of the cleverest and richest financiers in the world were wiped out.

As he emphasized again and again, the crucial skill lay not in knowing what property to buy or what company to invest in, but in reading the business and stock market cycle correctly. All his life he had been a contra-theorist, betting against the general view.

“If everybody agrees that you should increase capacity in ball bearings, for example, you can be absolutely sure that there’s going to be a glut of ball bearings, and you’ll end up losing money.”

While Sir James certainly had the gambler’s instinct, he was also a shrewd analyst and a voracious reader of economic and political columns, media and raw economic data from all over the world. He always sought opinions from those he respected, such as Nobel Peace Prize recipient Henry Kissinger, and never invested in the stock market without ringing half a dozen ‘experts’ and finding out whether they agreed with one another. He defined his personal market philosophy in this way: